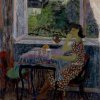

In 1948, Louis Van Lint is the first Belgian painter of his generation to create abstract works having a lyrical character (shortly before, Jo Delahaut had approached the geometric abstraction). Already, a work as Composition - Interior (Composition - Intérieur) hardly allows to perceive, under the ingenious partitioning of multicolored flat tints, a furnished interior. Various other objects then become also a pretext of eloquent formal arrangements where the elegant arabesque and the dialogue of contrasting colors prevail. However, starting this year, 48, it is principally the nature, a nature seen in the force of its primordial elements and perceived through the subjectivity of the artist, which will now lead the artist to some of the most inspired abstractions. In this regard, Heaven, sea and earth (Ciel, mer et terre), a canvas with merging waves and clouds, is the first significant step in the direction of this lyrical abstraction which will be the mark of the reputation and originality of Van Lint's art.

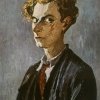

The artist ventures afterwards in a spontaneous style using the emergence of mobile and expansive signs, which appear as formal metaphors of the vegetal, organic, or cosmic nature (Music in hell, Musique en enfer). These signs, these kinds of elongated cells with curves closely intertwined but readily broken by angles, find their consistency and power of expression within the creative use of Fauves flat tints Symphony in Red (Symphonie en rouge), sometimes also in darker and monochrome tones Magical Composition (Composition magique). In 1950, such works are shown at the Palace of Fine Arts in Brussels, then in a Parisian Gallery and in Amsterdam in 1951. During these years, Van Lint is admired by his trainees of the COBRA group, also invited to participate in some of their exhibitions and activities. In 1949, he notably created his Magic Lantern (Lanterne magique), a stunning work, made of cut cardboard and cellophane, rotating (the first kinetic work in Belgium), projecting abstract forms. "Older and separated from the Danish influence, Van Lint is quite close to us and inspires us”, wrote the poet OJ Noiret from CoBrA. As early as 1951, the year when the Ministry of Culture asks the art critic Léon-Louis Sosset to write a first monograph consecrated to the artist, some paintings indicate the artist's desire to establish his reinvention of the real through serial compositions or insistent orthogonal, vertical, horizontal and oblique segments punctuating the canvas or gouache. There are also some works inspired by the stained glass windows of Chartres in the Royal Museum of Fine Arts in Antwerp, sometimes by an urban scaffolding, or, as in the wonderful Musical Composition (Composition musicale), by musical instruments. Shown in various international exhibitions, the works of this time bring to Van Lint a few prizes: in Santa Margherita-Liguria in 1950, in Lugano in 1952, and cause him to be sent by Belgium to the first International Biennial of Sao Paulo in 1951. This foundation within the abstract, does not stop Van Lint to create also figurative works, marked clearly by his fondness for abstract arrangements of shapes and colors Man Shaving, Self-portrait (Homme se rasant, autoportrait).